What is compassion? Compassion, as a concept, can be defined as "attending to the challenges of others, to feel empathy, sympathy, and sorrow for another who is experiencing difficulties and misfortune, and the desire to assist in alleviating their distress in solidarity with them” (1). It is a Buddhist concept that has existed for years but has only been given the attention it deserves in the last twenty years or so (5,10). It may be interesting to hear antonyms of compassion, which are in fact ‘heartlessness’, ‘indifference’ and ‘coldness’, to name a few. These strong, abstract nouns show how compassion is taking a kind but active interest in others’ pain to help reduce it. Interestingly, this can be for people we know as well as people we do not, opening the possibilities of how compassionate we can be as individuals (2). There can be confusion around the difference between compassion and other abstract nouns such as ‘empathy’ and ‘sympathy’, as they are often used synonymously or to define each other. To define empathy, “an empathetic person might or might not respond with a compassionate action when they take on and experience the emotions of another human being” and sympathy relates to being aware of someone’s experience but staying in a different emotional state (3). It is therefore less known that compassion, for others and yourself, is in fact a stand-alone skill that someone can develop and acquire through practice (4). What is self-compassion? Now that compassion has been defined, we can turn to self-compassion. Dr Kristin Neff, a pioneer in self-compassion research, defines it as “the process of turning compassion inward” (5). Like we would a friend, we address our mistakes, insecurities or fears with kindness and encouragement, in a non-judgemental way. When we do this, our chances of achieving our goals and growing as an individual increase greatly because we reduce the pressure we put on ourselves to be on ‘top form’ all of the time. One important note that Neff makes is that self-compassion is not the same as self-pity or self-indulgence; there are very different concepts.  Self-compassion is linked to self-love, self-esteem, self-kindness and many other forms of personal growth and development. Due to this, for someone to be a compassionate person, they must first understand and practice self-compassion, otherwise it is less likely that their compassion for others will be genuine (6). Although this seems harsh, consider situations you have been in where you have had to explain or demonstrate a skill or concept without time to practice or learn about it yourself. It is hard to adequately explain it or teach it to the other person in a way that is useful. Compassion works very much in the same way; therefore, it needs to practiced on ourselves before we can give it to others (6). Why do we need self-compassion?Research around self-compassion is growing as information on the concept’s benefits grows in popularity amongst psychologists, therapists, and health and wellbeing experts. Although there is still much to be discovered, there are commonalities in the research relating to the importance of self-compassion. According to Neff, “higher levels of self-compassion are linked to increased feelings of happiness, optimism, curiosity and connectedness, as well as decreased anxiety, depression, rumination and fear of failure” (7). Being a self-compassionate individual has also been linked to helping you become more of your authentic self, which is classified as being your ‘true self’ (8). By being able to accept yourself for who you are, through the use of kind words, understanding and patience, self-compassion can work as the internal friend you’ve always needed. Self-compassion in the context of University University life can be incredibly challenging at times, with competing deadlines, unfamiliar social situations, fears around delivering presentations and being assessed in a multitude of ways. This is aside from the external factors that impact on students such as work responsibilities, relationships, family life and of course, the repercussions of the Covid pandemic. It is therefore not hard to understand why so many students experience burnout and why we are amid a student mental health crisis (9, 11). Considering this, practicing self-compassion and other forms of self-care can help students feel more in control of their wellbeing, which will likely have a positive impact on their university experience. This is in part down to the students to take ownership of their wellbeing. But it is also the university’s responsibility, specifically the health and wellbeing team, to provide guidance, support and potentially courses relating to self-compassion and self-care (11). How can we give compassion?  Below are suggestions for how to give yourself and others compassion, taken from research. These may not work for everyone but they could be something to try if you are feeling overwhelmed, stressed or you are experiencing negative self-talk and negative thoughts.

Useful resources Podcasts

References

1) Plante, T.G. (2016). Compassion. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1055-1 2) Strauss, C. et al. (2016) “What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures,” Clinical Psychology Review, 47, pp. 15–27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004. 3) Compassion vs. empathy: What's the difference? - 2023 (no date) MasterClass. Available at: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/compassion-vs-empathy (Accessed: March 7, 2023). 4) Mascaro, J.S. et al. (2020) “Ways of Knowing Compassion: How Do We Come to know, understand, and measure compassion when we see it?,” Frontiers in Psychology, 11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.547241. (5) Neff, K.D. (2022) Self- compassion. Available at: https://self-compassion.org/ (Accessed: March 7, 2023). 6) How to practice self-compassion (article) (no date) Therapist Aid. Available at: https://www.therapistaid.com/therapy-article/how-to-practice-self-compassion (Accessed: March 8, 2023). (7) Neff, K.D. (2009) “The role of self-compassion in development: A healthier way to relate to oneself,” Human Development, 52(4), pp. 211–214. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000215071. (8) Zhang, J.W. et al. (2019) “A compassionate self is a true self? self-compassion promotes subjective authenticity,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(9), pp. 1323–1337. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218820914. 9) Warnings of mental health crisis among 'Covid generation' of students (2022) The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jun/28/warnings-of-mental-health-crisis-among-covid-generation-of-students (Accessed: March 8, 2023). 10) Neff, K.D. (2011) “Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), pp. 1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x. 11) The Mental Health Crisis in colleges and Universities (no date) Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/zero-generation-students/202302/the-mental-health-crisis-in-colleges-and-universities (Accessed: March 8, 2023). 12) Using Affirmations (no date) MindTools. Available at: https://www.mindtools.com/air49f4/using-affirmations (Accessed: March 8, 2023). 13) Affirmations (2015) Louise Hay. Available at: https://www.louisehay.com/forgiveness/ (Accessed: March 8, 2023).

0 Comments

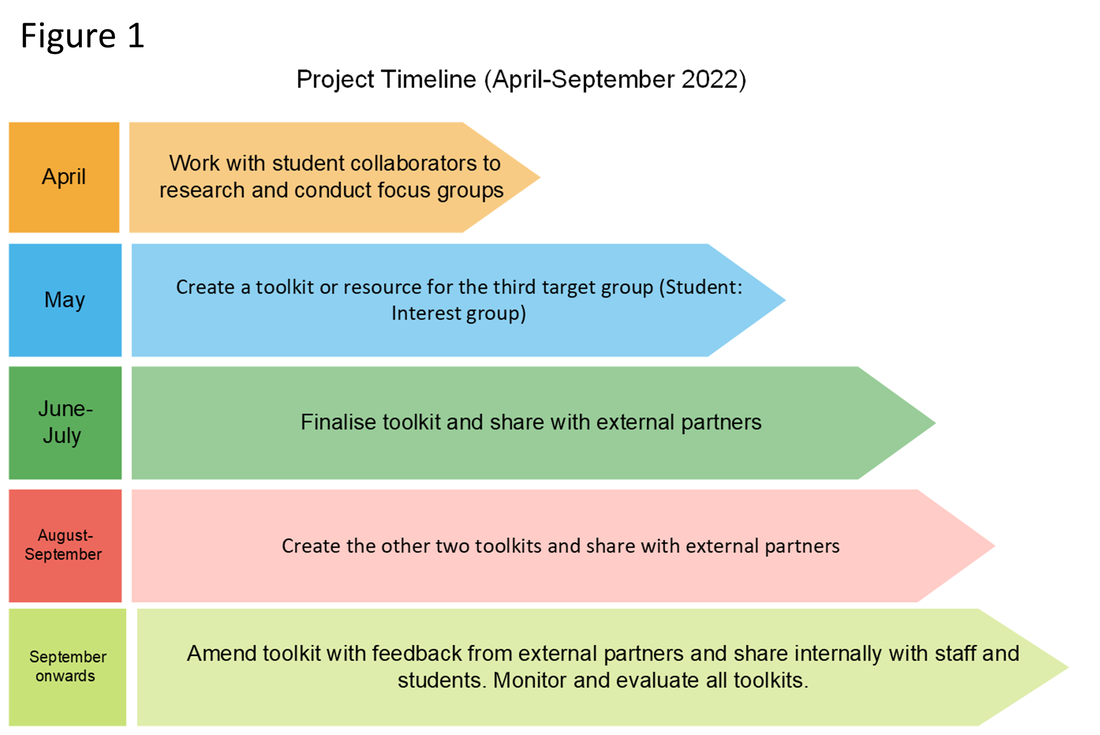

In Higher Education, 'co-creation', 'students as partners', 'collaborative partnerships', 'staff-student partnerships' all allude to the same thing: working with students on a level instead of instructing them from above. The practice has been around for about a decade (1) and Cook-Sather, Bovill and Felten (2) outline what co-creation is in more detail: “a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways… [for] conceptualisation, decision making, implementation, investigation, or analysis.” As part of the Positive Digital Practices project, a key aspect was the involvement of students. Within the University of Bradford’s Positive Digital Communities strand, we wanted students to be involved from the get-go to inform our toolkit. The Higher Education Academy (3) identify the different forms of student partnership and our project fits into the area of ‘subject-based research inquiry’. It does so by researching into what current practice occurs within the university and how we can support staff and students’ practice, and subsequently their experiences. The planning and recruitment phaseIt is important to establish a student: staff partnership model before the work commences to ensure successful implementation (1). To do this, I created a prospective timeline, alongside a project tracker, that would help outline the key responsibilities and targets of the project. This was shared with the students in our first meeting (see Figure 1). Alongside this, key themes from the literature that were relevant to our project goals, and the type of involvement the students would have, were identified (1,4):

These underpinned the way the students were managed and were referred to throughout. It was also important to offer both in-person and online meetings so that the work best suited the students’ needs. We decided on a mix of both meeting types, and we chose Teams as our preferred platform due to familiarity and ease of access. The students’ job title was chosen based on the project goals and the type of involvement the students would have in the project. I felt ‘Students as Active Collaborators’ encompassed the importance of student voice and effective engagement, something Healey, Flint and Harrington agree with (3,5). Our project focusses on the diversity of students and their university experiences, so listening to the student voice is essential for learning what they need and respond to (1). After deciding on the name, we started recruitment processes. We felt it important to pay the students instead of making their involvement voluntary, so that they felt part of the team. We had nine applicants, and of those, we recruited four. The creation and implementation phase As a team, we co-created a mutual agreement of values and expectations for the partnership, so all members were on the same page yet accountable for their actions. Using the above diagram, we then discussed how the next few months would pan out so we could account for deadlines, exams, and dissertation hand-ins. It was crucial that this role did not impede on their studies or other university requirements (6, 7). The students were involved in reading literature, conducting primary research, report writing and resource creation. A summarised list of activities that the students were involved are listed below (this is not exhaustive and does not account for the fortnightly meetings and catch-ups we had throughout their time on the project):

By enabling students, from different academic backgrounds, to be involved in such a project provided a rich and varied collection of resources. It minimised the traditional hierarchies that exist within an institution by removing the barriers between students and staff, and although they were tentative to begin with, by the end they were more than happy to share their views and say when they respectively disagreed with an idea. As Healey, Flint, and Harrington state (3), this improves a student's sense of belonging and helps them identify their place within the institution as not just a consumer but a contributor. The reflection phase To evaluate whether the role was appropriately challenging and was also meeting the students’ expectations, a mid-year, anonymous evaluation was conducted. When asked if they felt they had the opportunity to collaborate on the project, all of them stated yes, with one student going on to say: “Yes, I have had the opportunity to collaborate with different students and colleagues.” Demonstrating that they have had the chance to work with others outside the team too. The key themes that came through when asked what they have enjoyed the most includes interviewing students, creating the resources, and having the opportunity to collaborate with other students who are not on the same course as them. One student stated: “The most important lesson I've learnt is the importance of teamwork.” When asked what impact they think they have had, the main theme was supporting students and staff in the university through the creation of the resources and toolkit. The students also stated that they felt a sense of accomplishment that their hard work and involvement in the project will result in a better experience for staff and students and that their ideas and individual voices have been listened to. A challenge that was overcome throughout the students involvement was the lack of engagement in Teams. Communication was sometimes poor between the students and me, resulting in tasks not being completed by the given deadline. This was likely due to the time of year and the fact they had competing responsibilities such as assignments, exams, and dissertation hand-ins. This was overcome by creating a meeting action log so that they knew who the tasks were for and when they were due. On reflection, I feel both privileged and humbled to have worked with a dedicated, enthusiastic, and hard-working group of individuals who made the last six months fly by. The toolkit we have created is one to be proud of and it could not have been possible without their individual areas of expertise, knowledge, and creative thought. Co-creation is a worthwhile experience that I believe should be conducted much more regularly within Higher Education. References

This blog post was written by Sophie Jones-Tinsley, Positive Digital Practices Project Officer from the University of Bradford. A personal storyAs a person who lives with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), I am constantly fighting the symptoms of feeling intense anxiety. One symptom that can cause isolation is that of needing a routine and not liking change. When social plans are altered, I find it very hard to deal with and as a result I decide not to go. At 26, I can better deal with these emotions however at 18, when I first started University, it meant that many people branded me as anti-social, unreliable, and sometimes rude. Alongside this I was a commuter student, so I didn’t live on campus, and this added to the social exclusion I experienced from my peers. Due to all this I often felt lonely and that I didn’t belong, so I focused on my studies and missed out on the “typical” University experience. It wasn’t until I found a couple of people like me who I bonded with (and am still friends with to this day) that I started to enjoy University life. However, I will always look back and regret not joining a support group or peer community to talk and share my experience, in the chance that someone else was feeling the same and could help. Loneliness in young adultsLoneliness is a topic that not many people discuss, especially when it comes to loneliness amongst teenagers and young adults (the 16-24 bracket). Due to their age, it is deemed unlikely that those who are just starting out on their life journey, where being social and interacting with others is at its peak, would experience feeling lonely or isolated. However, this is far from the reality and students’ experiences of feeling lonely worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic. Last year, the Office for Students (OfS) conducted a survey around how Coronavirus had impacted students’ education across the UK. Startlingly, 26% of students reported feeling lonely often or always, compared with 8% of the adult population in Great Britain over a similar period[1]. Similarly, a study conducted in the same year by British Red Cross found the same result, with 26% of people aged 16-24 years old feeling lonely always or often[2]. The impact of loneliness on an individual’s mental wellbeing can be very damaging and research has shown that it can be associated with social isolation, poor social skills, introversion, and in some cases, depression[3]. Not only this, in the context of Higher Education, it can have an impact on an individual’s self-perception and self-worth, which can directly impact their ability to concentrate and focus on their studies and education[4]. How can this be tackled? At the University of Bradford, we are taking part in a project led by The Open University and funded by the OfS, which focuses on Positive Digital Practices. Our strand of the project is called ‘Positive Digital Communities’, which can be defined as online spaces where individuals can interact through sharing of information, shared interests, ideas, or beliefs[5]. Research has shown a direct link to combating and aiding loneliness through digital communities and the importance of utilising technology as a way of connecting with peers[6][7][8]. Below are a few examples of how digital communities can have a positive impact on students’ mental wellbeing and a subsequent impact on reducing their feelings of loneliness:

Digital communities of any kind can therefore be very rewarding, and I encourage you to reach out and share your experiences with others, because we’re more alike than people realise, and we can also help each other more than we realise. Sophie Jones-Tinsley works as a Project Officer at the University of Bradford on the Positive Digital Communities project. If you would like to find out more about the project and the work we are doing, please email: [email protected] References

[1] Coronavirus and higher education students - Office for National Statistics [2] Lonely-and-left-behind.pdf [3] Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet. 2018;391(10119):426. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9 [4] Brakespear, G. & Cachia, M., (2021) “Young adults dealing with loneliness at university”, New Vistas 7(1), p.31-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.36828/newvistas.23 [5] I. G. Publisher, “IGI Global,” [Online]. Available: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/creating-analytical-lens-understanding-digital/7583. [6] El Morr, C., Maule, C., Ashfaq, I., Ritvo, P., and Ahmed, F., (2020) “Design of a Mindfulness Virtual Community: A focus-group analysis”, Health Informatics Journal 2020, Vol. 26(3) 1560–1576 [7] Pimmer, C., Abiodun, R., Daniels, F., and Chipps, J., (2019) “I felt a sense of belonging somewhere”. Supporting graduates' job transitions with WhatsApp groups”, Nurse Education Today, Vol. 81 [8] Brakespear, G. & Cachia, M., (2021) “Young adults dealing with loneliness at university”, New Vistas 7(1), p.31-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.36828/newvistas.23 The Positive Digital Practices project has officially launched! We had our official kickoff meeting on Wed 8 September, where we all came together for the first time.

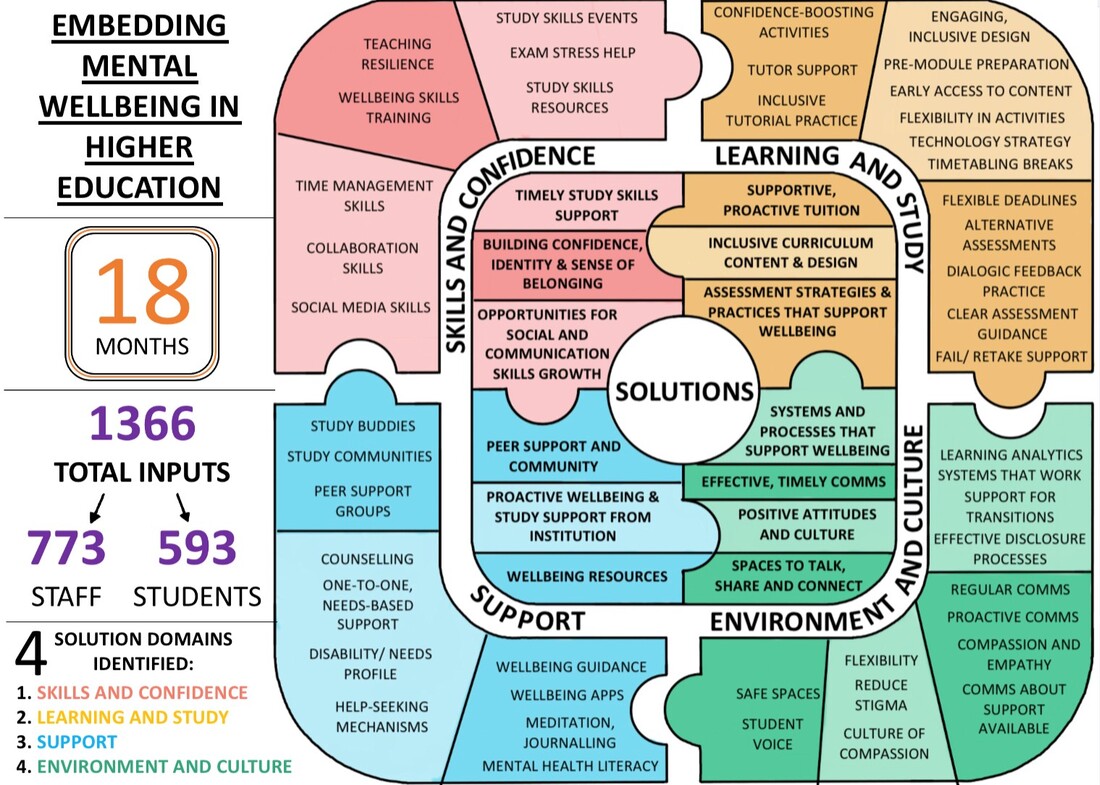

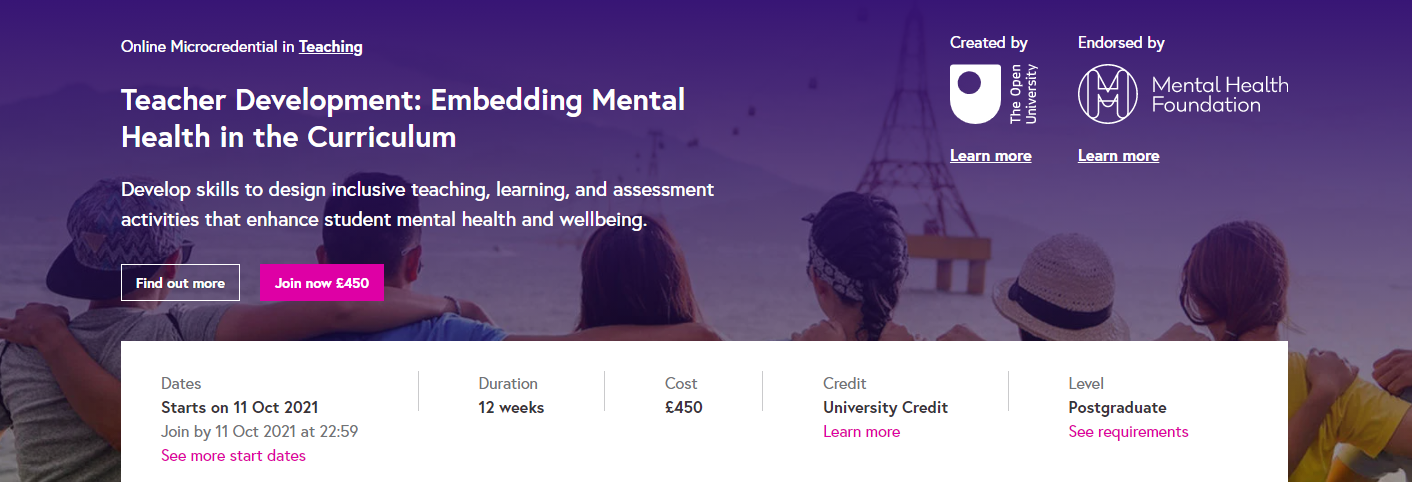

First, we agreed our project ethos and values. We're following a social model ethos, identifying (and addressing) barriers in environments rather than looking for deficits within people. We agreed that we value student and staff wellbeing, so we're building a supportive, positive working community, to make this a project that everyone can enjoy working on. Next, we talked though each of the work areas and work packages, and the plans for engaging with different stakeholders, identifying overlaps, synergies and opportunities to collaborate. This was an exciting part of the session, we discovered a lot of shared interests and passions! Finally, we talked about project logistics. Happily, all our approvals (Ethics, data protection, etc) are in place and recruitment for project members and our steering group is well underway. The next step now is to get started on our work packages - watch this space for updates!  Today's blog is courtesy of Psychreg.org, and was written by Kate Lister, lecturer at the Open University and project lead on Positive Digital Practices. Access the original article. Student mental well-being is a critical concern in higher education. The number of students disclosing mental health difficulties is increasing year on year, and statistics show consistent and concerning gaps in degree outcomes for students with mental health issues. This is particularly the case in distance learning. Even before the pandemic, distance learning students appear more likely than campus-based students to disclose mental health difficulties and may be more likely to need support. In the Open University (OU), 12.2% of students (16,139 in total) disclosed a mental health condition in 2019–20, compared to the UK sector average of 4.2%, and the OU’s Access and Participation Plan shows worrying gaps in degree outcomes for students with mental health difficulties. There is a need for universities to take action. Studies have found that academic pressure and university culture and systems may be triggering mental health issues, and that mental well-being for students is consistently worse than the well-being of non-students of comparative age. Sector bodies and charities like Student Minds are increasing calling for universities to take a whole-institution approach to embed mental well-being throughout practice. Embedding well-being in distance learningA three-year initiative in the OU is working towards embedding mental well-being in distance learning. Working with staff and students across the university, it aims to identify barriers and enablers to well-being that students experience, and co-create solutions that can be embedded in practice to address these barriers. First, 16 students and 5 tutors took part in interviews; this identified a taxonomy of barriers and enablers to well-being in distance learning. Next, focus group events were held with 116 OU staff and students, and surveys were sent to wider groups of staff and students. These aimed to seek broader perspectives on barriers and enablers, and to generate ideas for solutions that might address the barriers in practice. In total, 773 staff and 593 students created 806 ideas for solutions. These broadly fell into four categories: skills and confidence, learning and study, support, and environment, and culture. Focus group events worked to turn ideas into projects. In the third year of the initiative, five projects were piloted in practice. These included: Well-being in learning design Our study identified a number of examples of positive pedagogy that supported student well-being, but these were inconsistently applied in practice. This project aimed to embed positive practice in the OU’s Learning Design approach, building well-being into the design of module structure, activities and assessment through a series of recommendations to module teams in production. Recommendations included flexibility, scaffolding of challenging activities (such as group work), and embedding content on mental health. The project team worked with a student panel to hone and refine the recommendations, and these are currently being piloted with modules in production. Discipline-specific well-being resource hubs Students in our study told us that wellbeing guidance tended to be rather general, and to reside in student support areas rather than be part of their study environment. This meant they frequently didn’t find it until they had a real problem, rather than using it to head off a problem before it became serious. This project aimed to address this by creating hubs of discipline-specific well-being guidance and resources for students, curated for the programme they were studying and hosted on programme ‘Study Home’ websites. The project team worked with staff across the university to agree a shared structure and example resources (for example: resources on study meditation, exam stress, maths anxiety, placement difficulties, etc.). Technical teams then created ‘Your well-being’ webpages on Study Home sites across the OU; these launched in March 2021 with generic content, and will be slowly customised by programme teams with bespoke, programme-specific content. Distressing content and emotional resilience Our study recognised the difficulties that distressing curriculum content can present for students, especially when it triggers flashbacks or reminders of trauma. This project aimed to support academic module teams to ensure that any potentially distressing content in their curricula were properly scaffolded, with content warnings, guidance for students and delivered using a pedagogy of care. The project team first carried out a review of modules containing potentially distressing content. A working group then devised a banding system to classify content. Category A topics required the most signposting and support as these can trigger harmful behaviours in students; these include topics such as suicide, eating disorders and self-harm. Category B contains topics that may trigger flashbacks of trauma, such as abuse, rape, hate crime, violence or psychosis. Category C contain topics that may be painful or distressing, such as animal cruelty, death and common phobias. The team then worked with stakeholders across the university to create a standard approach to signposting, content warnings and supporting guidance for the three categories, including template guidance and wording module teams could use. This approach has been implemented in all new modules, and editors are currently working to incorporate it into existing modules. Well-being in tuition Our study found that support from tutors is a critical part of student wellbeing in distance learning. This project aimed to scale up positive tuition practice by working closely with academic tutors in one faculty. First, the project team worked with a small group of tutors and students to co-create an ‘inclusivity audit’ tool that tutors could use to analyse how well represented mental well-being was in their tuition practice and materials. Next, it piloted this tool with a range of tutors in the faculty, accompanied by specialist training on student mental well-being, challenges students can face, and the impact positive tuition can have. This was extremely popular and resulted in a number of completed ‘audits’ that other tutors could draw on for inspiration. Finally, the team worked with students to create a set of student videos, sharing their experiences of mental health challenges and achievements in distance learning. These videos, along with the inclusivity audit tool and examples of completed audits, were shared with tutors across the faculty, and are currently being rolled out to other faculties in the OU. Well-being in the curriculum professional development The findings from the study, and recommendations for practice in embedding wellbeing in curriculum and assessment, were compiled into a professional development micro-credential. Endorsed by the Mental Health Foundation, this 12-week course shares current literature, findings from the study, and practical guidance for educators in all contexts on how to ensure their practice both supports and promotes student wellbeing. Over 250 practitioners have taken the course so far. Towards embeddednessThese projects are the first steps in a journey towards embedding mental wellbeing in distance learning. These pilot projects will be evaluated, successful initiatives will be scaled up, and other solutions will be piloted. Students and staff from across the university will be involved throughout, and new funding from Office for Students has brought exciting partnerships with sector bodies and other universities, moving towards more inclusive distance learning environments.

Learn more about the OU project, access the original article or discover new articles on Psychreg.

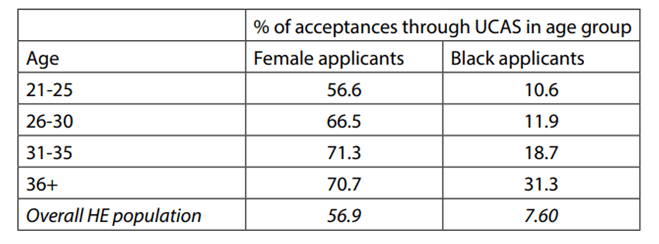

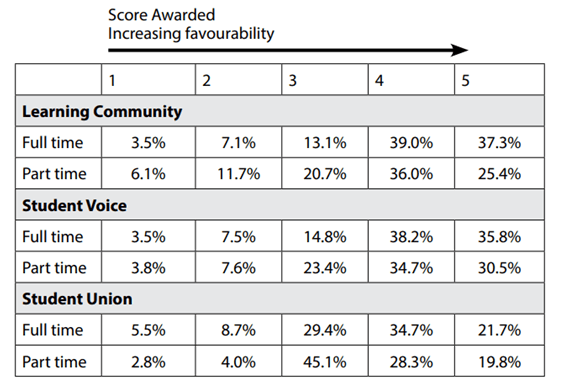

Undergraduate students become officially ‘mature’ if they commence their course aged 21 or over; for postgraduates it is over the age of 25. Currently 39 per cent of undergraduate entrants and 50 per cent of postgraduates are mature at UK universities. Despite this, there remains a prevalent ‘young student’ narrative in society, with mature students remaining comparatively unseen and unheard. How can this be explained and addressed? Who are they? It is not surprising that mature learners are more likely to have family or caring responsibilities, have a disability or come from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Table 1 illustrates that with increasing age, mature students are more likely to be Black and female. How and where do they study? A significant proportion of mature students are also ‘non-traditional’ in other ways. The proportion of mature students studying part-time is over five times that of young students, for both undergraduates and postgraduates. A fifth of mature undergraduates study with the Open University. Distance learners are the ultimate unseen students: they are not seen on campus, they rarely show any markers of student identity and they do not live in student accommodation. Mature students are far from uniformly distributed across qualifications or providers. Those who applied via UCAS reportedly favoured lower-tariff providers and a smaller range of courses. By far the most popular are Education and Subjects Allied to Medicine. Students studying for Level 4 or 5 qualifications are also disproportionately mature (79 per cent). Mature students also have less good outcomes, are more likely to drop out and, when full-time, they gain fewer higher classification degrees than young students. Mature students and the National Student Survey (NSS) The NSS is admittedly an imperfect instrument, but its role in the student voice cannot be ignored. Although collective data is not released for mature students, given that 89 per cent of part-time students are mature, part-time vs full-time is a reasonable proxy. The aggregated data show a stark difference in response rate – 70.4 per cent for full-time but 55.9 per cent for part-time. This does not tell the full story: the exclusion of subject areas and providers that fail to reach the 50 per cent threshold will tend to disenfranchise courses with many part-timers as they are less likely to be the ‘beneficiaries’ of on-campus NSS drives. One example is the Open University having narrowly missed the inclusion threshold in 2020, despite the raw numbers responding being higher than those at many included institutions. Despite this incompleteness, the responses of part-time learners are telling. Table 2 shows the relevant responses. ‘Learning community’ is included as the best proxy for a sense of belonging. Belonging underpins effective student voice. The very marked differences in this measure would alone hint not all is well. It is also apparent the responding part-timers are less positive about their student union’s academic representation and student voice in general.

Combining the notoriously low turnout for students’ union elections with the NSS data might feed into the hostile response to students’ unions and the Government’s allegations of ‘niche activism’. The huge efforts put in by sabbatical officers, working long hours on low pay to look out for their members, most certainly do not deserve this condemnation. But something is not working. What is going on? Why are mature learners not heard? It is a complex picture. Practicalities are crucial. Mature learners are typically time-poor, whether due to family or caring duties, fulltime employment or the demanding and time-consuming placements on the medically-related courses so popular with this cohort. Part-timers, in particular, are more likely to have focused brief visits to campus. Fitting in their studies is a juggling act; ‘inessentials’ will not merit time or mental resources. So anything perceived as peripheral, even giving basic feedback, is likely to suffer. But even if the practical issues were dealt with, how far do mature learners feel motivated and empowered to use their voices? The purpose of feedback is largely to improve things for the future. Offering feedback requires identifying with the institution – a sense of belonging. This concept is difficult to quantify and perhaps even more demanding to develop purposefully, but that does not render it any less crucial. Not only can being in a less visible group in an institution lead students to feel their contribution will not be valued by the institution, but also that it is not in itself valuable. It is not uncommon to hear mature students commenting along the lines ‘Get the young ones involved – they are who the university should hear from’ or ‘I am too distant from the normal students’. There is also some evidence of differences by subject, with healthcare students (many of whom are mature) exhibiting less sense of belonging. One powerful student voice mechanism is feeding into student representatives, or indeed becoming a representative. In many institutions, candidates for these roles are typically young students rather than mature students and those getting involved are often in informal networks with existing ‘insiders’. While representatives may be very willing to hear and amplify the voices of students in different demographics, that does not alone remove perceived barriers. A further issue is the perceived value of student voice. Incentivising completion of the National Student Survey (NSS) or course questionnaires is common; this may seem an obvious short-term strategy but it is an established psychological phenomenon that incentivisation tends to reduce perceived intrinsic value. Furthermore, if the student voice becomes a matter of delivering quotable statistics, students will understandably feel their institution aims to profit from their labour rather than genuinely wishing to listen to them. The mature student who already feels somewhat ‘othered’ is unlikely to want to be crowded into a hall with their younger peers to do what feels like a tick-box survey in return for pizza. What can be done? The high proportion of mature students who are ‘non-traditional’ in other respects suggests that solutions to their voices may pay dividends with other missing voices too. There is a need to move away from a deficit model which sees mature students in terms of the issues or difficulties they have. Mature students have life experiences they can bring to the university, for example their ability to prioritise and manage their time are often extremely well honed by necessity. These should be actively valued. The sheer courage of tackling studying when you are atypical should be celebrated. A starting point is a ‘Universal Design for Student Voice’, in which approaches to encourage and facilitate marginalised voices are embedded right at the start, rather than as a bolton to a mechanism focused on young full-timers. As a starting point, this requires flexible and remote opportunities as the default. Many students’ unions are rightly aiming to increase the diversity of the students who engage with them, and vital as this is, it is not necessarily going to be a quick win. So, without undermining their students’ unions, universities need to explore additional mechanisms for students to use their voices. If mature students see their feedback valued by the university, that may itself encourage them to consider a more formal role. University staff need to appreciate that encouraging the voice of non-traditional students may require different approaches. If diversity is to be increased, and mature students empowered to engage, then barriers need to be removed. Even students’ unions officers may find university governance impenetrable at times and have concerns about power imbalances, as Eve Alcock outlines in this collection. How much worse are these issues for non-traditional students? Routes in, other than formal and potentially intimidating ones, need to be developed. This does not mean staff being patronising or making ‘therethere’ noises, but it does entail openness and treating students with respect, as fellow adults. This author had one experience of being blatantly patronised and laughed it off. For a less confident mature student, it could mean their first foray into using their voice was their last. Moving student voice past the simple ‘feedback’ model towards real partnership and valuing experience and insight could pay dividends. And be prepared to pay students for their labour – not with pizza, but on a financial basis, as consultants. For mature students in particular, time is money. It's launch day! Office for Students have just published their funding competition press release, so Positive Digital Practices is an official, live, funded project!

Now it's all official, we're excited to launch the Positive Digital Practices project website and blog. This will be a space for general project information, informal project updates and for trialling new outputs, guidance and resources that we create in the project. Blogs will be written by staff and students across the project, and we're always happy to host guest blogs featuring other perspectives or insights into mental wellbeing for distance, part-time or commuter students (if you'd like to do this, do get in touch!) Feel free to leave comments or to email [email protected] for more information. |

AuthorsBlogs from across the Positive Digital Practices project team Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed